Prints (370)

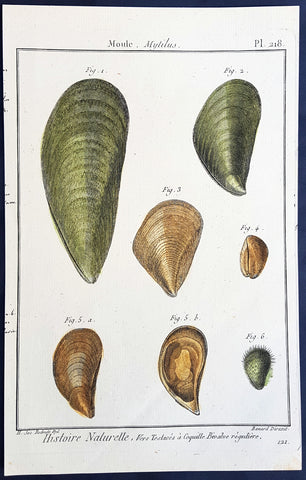

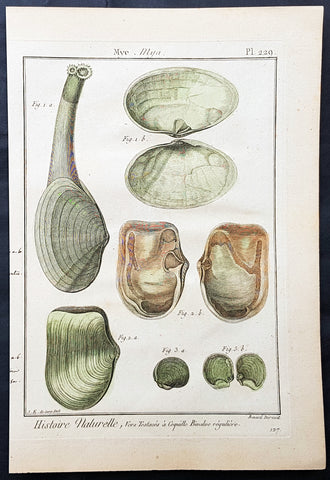

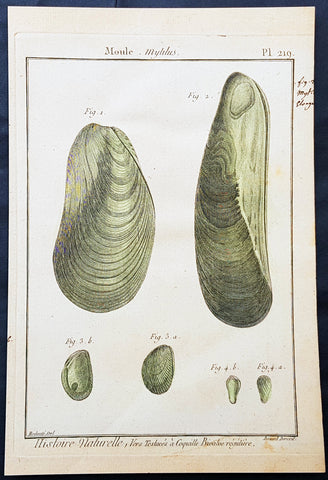

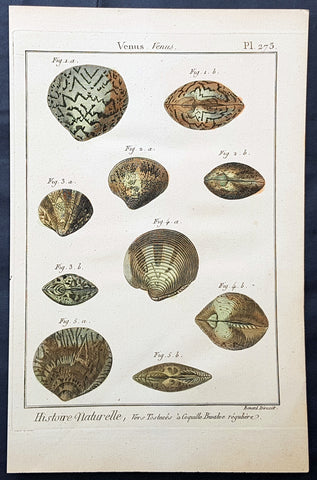

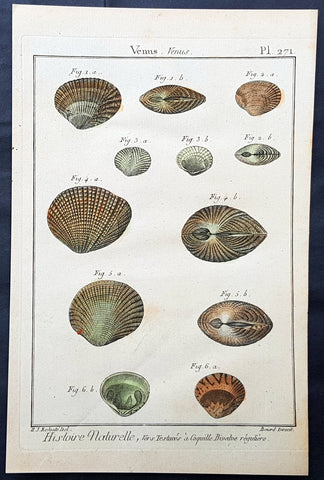

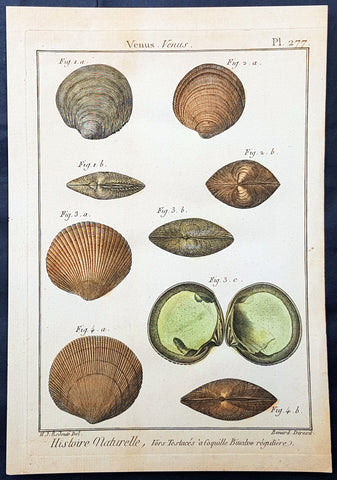

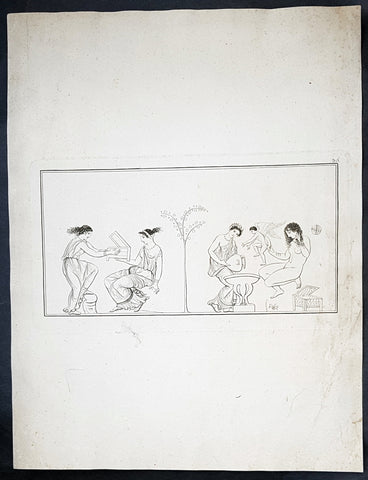

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Mussel Shells - Pl 218

- Title : Moule, Mytilus

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 205mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23849

Description:

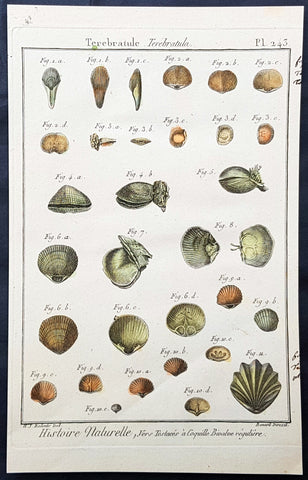

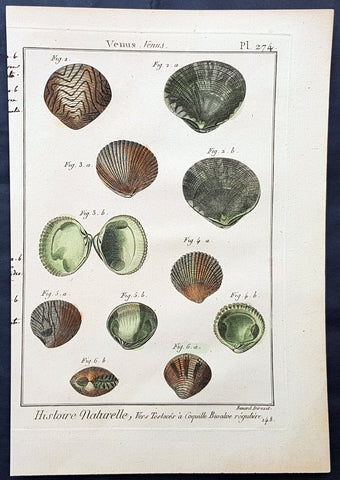

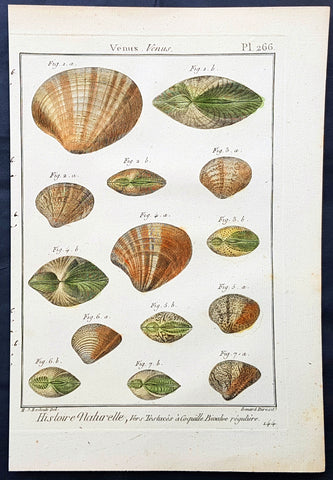

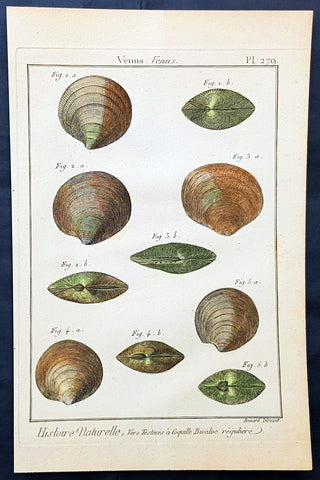

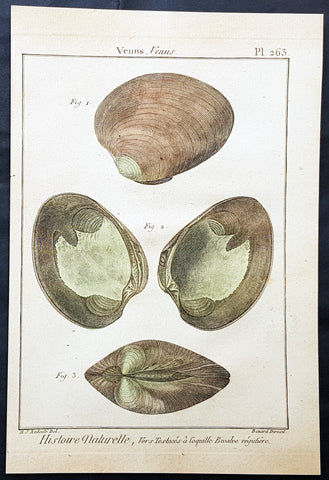

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 205mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.

With Buffons support, Lamarck was elected to the Academy of Sciences in 1779. Two years later Buffon named Lamarck correspondent of the Jardin du Roi, evidently to give Lamarck additional status while he escorted Buffons son on a scientific tour of Europe. This provided Lamarck with his first official connection, albeit an unsalaried one, with the Jardin du Roi. Shortly after Buffons death in 1788, his successor, Flahault de la Billarderie, created a salaried position for Lamarck with the title of botanist of the King and keeper of the Kings herbaria.

Between 1783 and 1792 Lamarck published three large botanical volumes for the Encyclopédie méthodique (Methodical Encyclopaedia) , a massive publishing enterprise begun by French publisher Charles-Joseph Panckoucke in the late 18th century. Lamarck also published botanical papers in the Mémoires of the Academy of Sciences. In 1792 he cofounded and coedited a short-lived journal of natural history, the Journal dhistoire naturelle.

Lamarcks career changed dramatically in 1793 when the former Jardin du Roi was transformed into the Muséum National dHistoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). In the changeover, all 12 of the scientists who had been officers of the previous establishment were named as professors and coadministrators of the new institution; however, only two professorships of botany were created. The botanists Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines held greater claims to these positions, and Lamarck, in a striking shift of responsibilities, was made professor of the insects, worms, and microscopic animals. Although this change of focus was remarkable, it was not wholly unjustified, as Lamarck was an ardent shell collector. Lamarck then set out to classify this large and poorly analyzed expanse of the animal kingdom. Later he would name this group animals without vertebrae and invent the term invertebrate. By 1802 Lamarck had also introduced the term biology.

This challenge would have been enough to occupy the energies of most naturalists; however, Lamarcks intellectual aspirations ran well beyond that of reforming invertebrate classification. In the 1790s he began promoting the broad theories of physics, chemistry, and meteorology that he had been nurturing for almost two decades. He also began thinking about Earths geologic history and developed notions that he would eventually publish under the title of Hydrogéologie (1802). In his physico-chemical writings, he advanced an old-fashioned, four-element theory that was self-consciously at odds with the revolutionary advances of the emerging pneumatic chemistry of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. His colleagues at the Institute of France (the successor to the Academy of Sciences) saw Lamarcks broad theorizing as unscientific system building. Lamarck in turn became increasingly scornful of scientists who preferred small facts to larger, more important ones. He began to characterize himself as a naturalist-philosopher, a person more concerned with the broader processes of nature than the details of the chemists laboratory or naturalists closet.

In 1800 Lamarck first set forth the revolutionary notion of species mutability during a lecture to students in his invertebrate zoology class at the National Museum of Natural History. By 1802 the general outlines of his broad theory of organic transformation had taken shape. He presented the theory successively in his Recherches sur lorganisation des corps vivans (1802; Research on the Organization of Living Bodies), his Philosophie zoologique (1809; Zoological Philosophy), and the introduction to his great multivolume work on invertebrate classification, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815–22; Natural History of Invertebrate Animals) . Lamarcks theory of organic development included the idea that the very simplest forms of plant and animal life were the result of spontaneous generation. Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first the power of life, or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex, whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment). He explained this in his Philosophie zoologique : The state in which we now see all the animals is on the one hand the product of the increasing composition of organization, which tends to form a regular gradation, and on the other hand that of the influences of a multitude of very different circumstances that continually tend to destroy the regularity in the gradation of the increasing composition of organization.

With this theory, Lamarck offered much more than an account of how species change. He also explained what he understood to be the shape of a truly natural system of classification of the animal kingdom. The primary feature of this system was a single scale of increasing complexity composed of all the different classes of animals, starting with the simplest microscopic organisms, or infusorians, and rising up to the mammals. The species, however, could not be arranged in a simple series. Lamarck described them as forming lateral ramifications with respect to the general masses of organization represented by the classes. Lateral ramifications in species resulted when they underwent transformations that reflected the diverse, particular environments to which they had been exposed.

By Lamarcks account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits. The basic idea of the inheritance of acquired characters had originated with Anaxagoras, Hippocrates, and others, but Lamarck was essentially the first naturalist to argue at length that the long-term operation of this process could result in species change.

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively Lamarckian view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited). The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarcks idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organisms lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.

Lamarck made his most important contributions to science as a botanical and zoological systematist, as a founder of invertebrate paleontology, and as an evolutionary theorist. In his own day, his theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Nonetheless, Lamarck stands out in the history of biology as the first writer to set forth—both systematically and in detail—a comprehensive theory of organic evolution that accounted for the successive production of all the different forms of life on Earth.

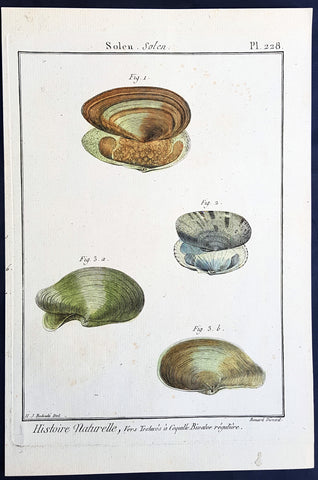

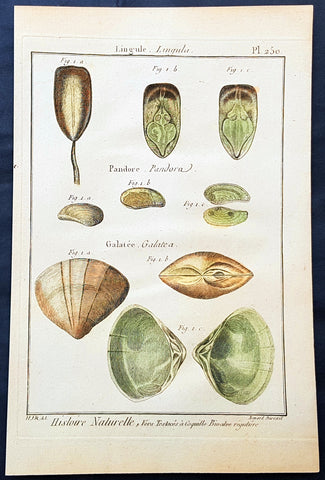

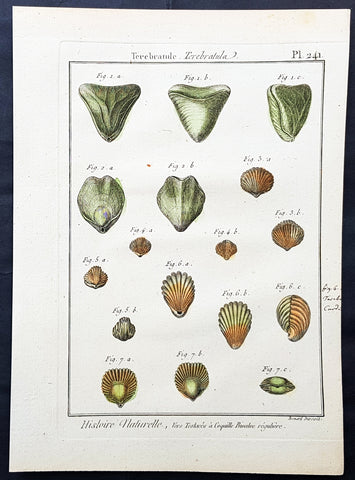

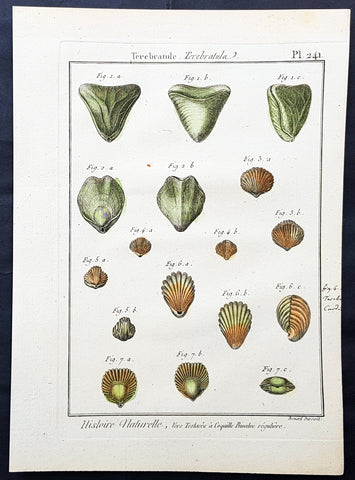

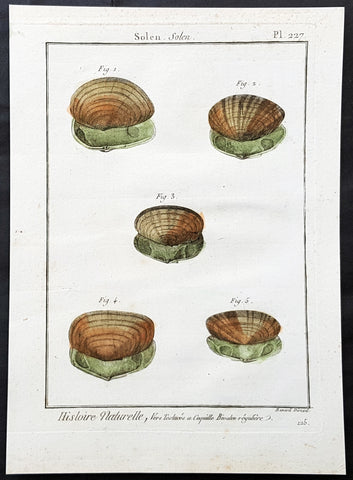

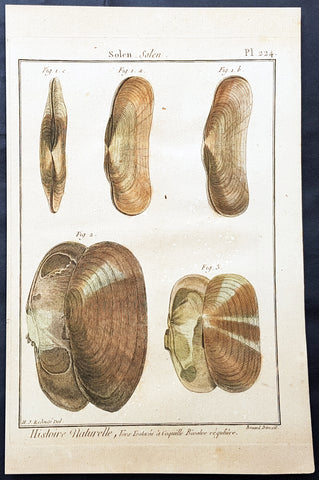

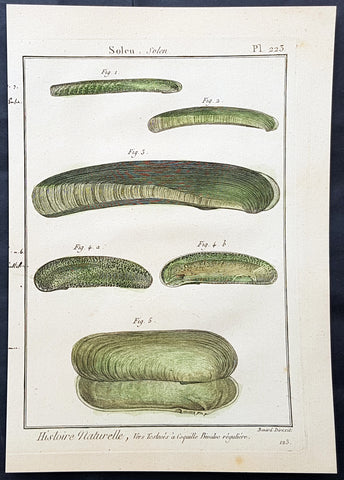

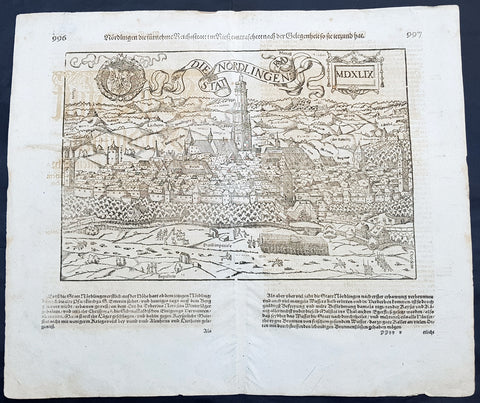

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Seawater Clam Shells, Pl 228

- Title : Solen, Solen

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 205mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23859

Description:

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 205mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.

With Buffons support, Lamarck was elected to the Academy of Sciences in 1779. Two years later Buffon named Lamarck correspondent of the Jardin du Roi, evidently to give Lamarck additional status while he escorted Buffons son on a scientific tour of Europe. This provided Lamarck with his first official connection, albeit an unsalaried one, with the Jardin du Roi. Shortly after Buffons death in 1788, his successor, Flahault de la Billarderie, created a salaried position for Lamarck with the title of botanist of the King and keeper of the Kings herbaria.

Between 1783 and 1792 Lamarck published three large botanical volumes for the Encyclopédie méthodique (Methodical Encyclopaedia) , a massive publishing enterprise begun by French publisher Charles-Joseph Panckoucke in the late 18th century. Lamarck also published botanical papers in the Mémoires of the Academy of Sciences. In 1792 he cofounded and coedited a short-lived journal of natural history, the Journal dhistoire naturelle.

Lamarcks career changed dramatically in 1793 when the former Jardin du Roi was transformed into the Muséum National dHistoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). In the changeover, all 12 of the scientists who had been officers of the previous establishment were named as professors and coadministrators of the new institution; however, only two professorships of botany were created. The botanists Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines held greater claims to these positions, and Lamarck, in a striking shift of responsibilities, was made professor of the insects, worms, and microscopic animals. Although this change of focus was remarkable, it was not wholly unjustified, as Lamarck was an ardent shell collector. Lamarck then set out to classify this large and poorly analyzed expanse of the animal kingdom. Later he would name this group animals without vertebrae and invent the term invertebrate. By 1802 Lamarck had also introduced the term biology.

This challenge would have been enough to occupy the energies of most naturalists; however, Lamarcks intellectual aspirations ran well beyond that of reforming invertebrate classification. In the 1790s he began promoting the broad theories of physics, chemistry, and meteorology that he had been nurturing for almost two decades. He also began thinking about Earths geologic history and developed notions that he would eventually publish under the title of Hydrogéologie (1802). In his physico-chemical writings, he advanced an old-fashioned, four-element theory that was self-consciously at odds with the revolutionary advances of the emerging pneumatic chemistry of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. His colleagues at the Institute of France (the successor to the Academy of Sciences) saw Lamarcks broad theorizing as unscientific system building. Lamarck in turn became increasingly scornful of scientists who preferred small facts to larger, more important ones. He began to characterize himself as a naturalist-philosopher, a person more concerned with the broader processes of nature than the details of the chemists laboratory or naturalists closet.

In 1800 Lamarck first set forth the revolutionary notion of species mutability during a lecture to students in his invertebrate zoology class at the National Museum of Natural History. By 1802 the general outlines of his broad theory of organic transformation had taken shape. He presented the theory successively in his Recherches sur lorganisation des corps vivans (1802; Research on the Organization of Living Bodies), his Philosophie zoologique (1809; Zoological Philosophy), and the introduction to his great multivolume work on invertebrate classification, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815–22; Natural History of Invertebrate Animals) . Lamarcks theory of organic development included the idea that the very simplest forms of plant and animal life were the result of spontaneous generation. Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first the power of life, or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex, whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment). He explained this in his Philosophie zoologique : The state in which we now see all the animals is on the one hand the product of the increasing composition of organization, which tends to form a regular gradation, and on the other hand that of the influences of a multitude of very different circumstances that continually tend to destroy the regularity in the gradation of the increasing composition of organization.

With this theory, Lamarck offered much more than an account of how species change. He also explained what he understood to be the shape of a truly natural system of classification of the animal kingdom. The primary feature of this system was a single scale of increasing complexity composed of all the different classes of animals, starting with the simplest microscopic organisms, or infusorians, and rising up to the mammals. The species, however, could not be arranged in a simple series. Lamarck described them as forming lateral ramifications with respect to the general masses of organization represented by the classes. Lateral ramifications in species resulted when they underwent transformations that reflected the diverse, particular environments to which they had been exposed.

By Lamarcks account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits. The basic idea of the inheritance of acquired characters had originated with Anaxagoras, Hippocrates, and others, but Lamarck was essentially the first naturalist to argue at length that the long-term operation of this process could result in species change.

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively Lamarckian view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited). The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarcks idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organisms lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.

Lamarck made his most important contributions to science as a botanical and zoological systematist, as a founder of invertebrate paleontology, and as an evolutionary theorist. In his own day, his theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Nonetheless, Lamarck stands out in the history of biology as the first writer to set forth—both systematically and in detail—a comprehensive theory of organic evolution that accounted for the successive production of all the different forms of life on Earth.

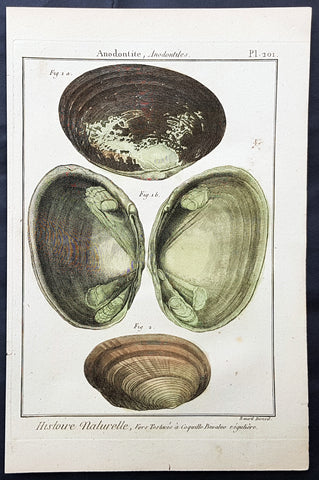

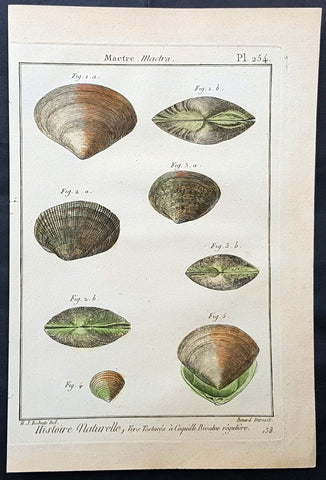

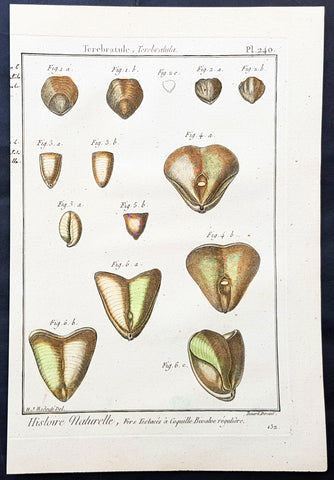

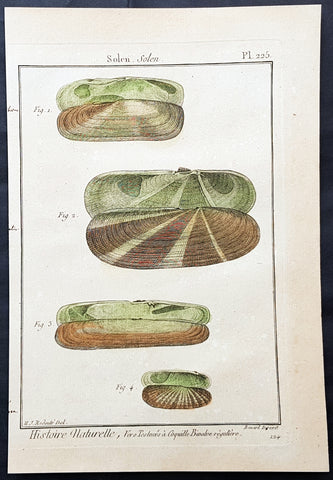

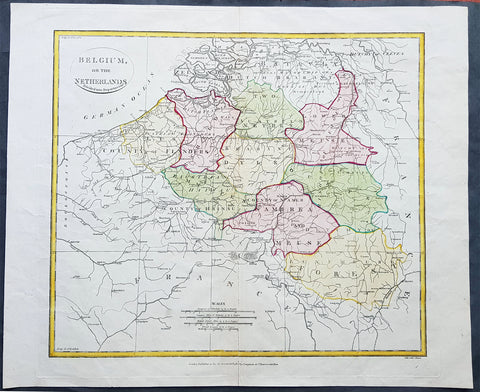

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Saltwater Clam Shells, Plate 201

- Title : Anodontites, Anodontites

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23832

Description:

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.

With Buffons support, Lamarck was elected to the Academy of Sciences in 1779. Two years later Buffon named Lamarck correspondent of the Jardin du Roi, evidently to give Lamarck additional status while he escorted Buffons son on a scientific tour of Europe. This provided Lamarck with his first official connection, albeit an unsalaried one, with the Jardin du Roi. Shortly after Buffons death in 1788, his successor, Flahault de la Billarderie, created a salaried position for Lamarck with the title of botanist of the King and keeper of the Kings herbaria.

Between 1783 and 1792 Lamarck published three large botanical volumes for the Encyclopédie méthodique (Methodical Encyclopaedia) , a massive publishing enterprise begun by French publisher Charles-Joseph Panckoucke in the late 18th century. Lamarck also published botanical papers in the Mémoires of the Academy of Sciences. In 1792 he cofounded and coedited a short-lived journal of natural history, the Journal dhistoire naturelle.

Lamarcks career changed dramatically in 1793 when the former Jardin du Roi was transformed into the Muséum National dHistoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). In the changeover, all 12 of the scientists who had been officers of the previous establishment were named as professors and coadministrators of the new institution; however, only two professorships of botany were created. The botanists Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines held greater claims to these positions, and Lamarck, in a striking shift of responsibilities, was made professor of the insects, worms, and microscopic animals. Although this change of focus was remarkable, it was not wholly unjustified, as Lamarck was an ardent shell collector. Lamarck then set out to classify this large and poorly analyzed expanse of the animal kingdom. Later he would name this group animals without vertebrae and invent the term invertebrate. By 1802 Lamarck had also introduced the term biology.

This challenge would have been enough to occupy the energies of most naturalists; however, Lamarcks intellectual aspirations ran well beyond that of reforming invertebrate classification. In the 1790s he began promoting the broad theories of physics, chemistry, and meteorology that he had been nurturing for almost two decades. He also began thinking about Earths geologic history and developed notions that he would eventually publish under the title of Hydrogéologie (1802). In his physico-chemical writings, he advanced an old-fashioned, four-element theory that was self-consciously at odds with the revolutionary advances of the emerging pneumatic chemistry of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. His colleagues at the Institute of France (the successor to the Academy of Sciences) saw Lamarcks broad theorizing as unscientific system building. Lamarck in turn became increasingly scornful of scientists who preferred small facts to larger, more important ones. He began to characterize himself as a naturalist-philosopher, a person more concerned with the broader processes of nature than the details of the chemists laboratory or naturalists closet.

In 1800 Lamarck first set forth the revolutionary notion of species mutability during a lecture to students in his invertebrate zoology class at the National Museum of Natural History. By 1802 the general outlines of his broad theory of organic transformation had taken shape. He presented the theory successively in his Recherches sur lorganisation des corps vivans (1802; Research on the Organization of Living Bodies), his Philosophie zoologique (1809; Zoological Philosophy), and the introduction to his great multivolume work on invertebrate classification, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815–22; Natural History of Invertebrate Animals) . Lamarcks theory of organic development included the idea that the very simplest forms of plant and animal life were the result of spontaneous generation. Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first the power of life, or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex, whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment). He explained this in his Philosophie zoologique : The state in which we now see all the animals is on the one hand the product of the increasing composition of organization, which tends to form a regular gradation, and on the other hand that of the influences of a multitude of very different circumstances that continually tend to destroy the regularity in the gradation of the increasing composition of organization.

With this theory, Lamarck offered much more than an account of how species change. He also explained what he understood to be the shape of a truly natural system of classification of the animal kingdom. The primary feature of this system was a single scale of increasing complexity composed of all the different classes of animals, starting with the simplest microscopic organisms, or infusorians, and rising up to the mammals. The species, however, could not be arranged in a simple series. Lamarck described them as forming lateral ramifications with respect to the general masses of organization represented by the classes. Lateral ramifications in species resulted when they underwent transformations that reflected the diverse, particular environments to which they had been exposed.

By Lamarcks account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits. The basic idea of the inheritance of acquired characters had originated with Anaxagoras, Hippocrates, and others, but Lamarck was essentially the first naturalist to argue at length that the long-term operation of this process could result in species change.

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively Lamarckian view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited). The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarcks idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organisms lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.

Lamarck made his most important contributions to science as a botanical and zoological systematist, as a founder of invertebrate paleontology, and as an evolutionary theorist. In his own day, his theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Nonetheless, Lamarck stands out in the history of biology as the first writer to set forth—both systematically and in detail—a comprehensive theory of organic evolution that accounted for the successive production of all the different forms of life on Earth.

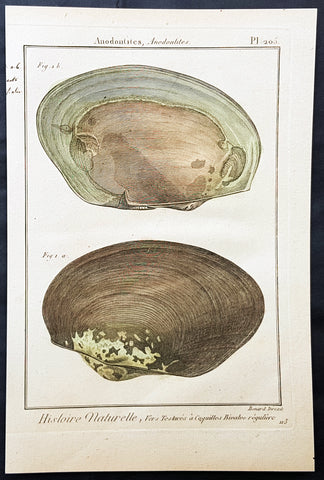

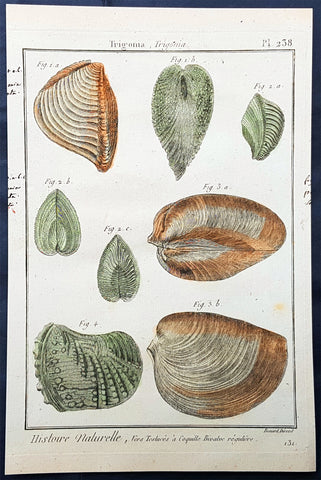

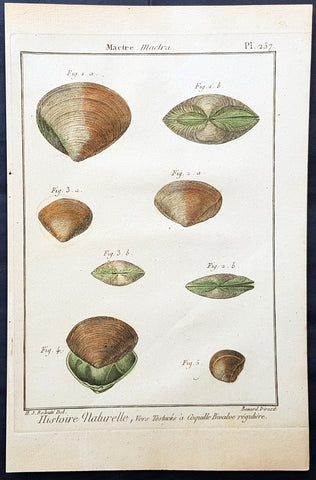

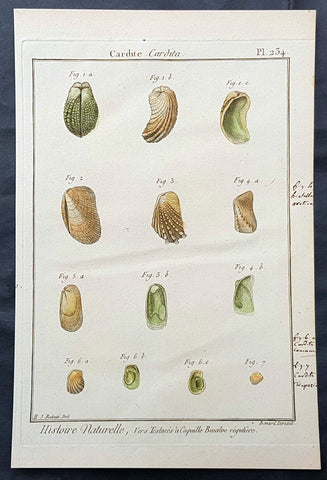

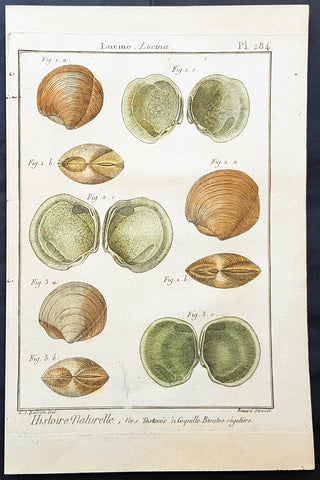

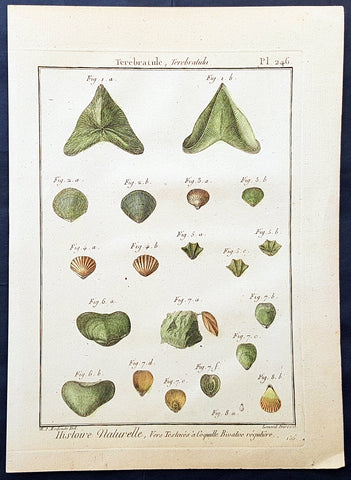

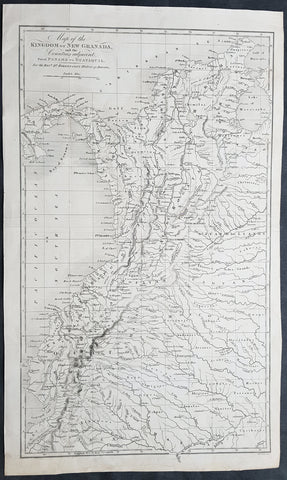

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Saltwater Clam Shells, Plate 205

- Title : Anodontites, Anodontites

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23836

Description:

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.

With Buffons support, Lamarck was elected to the Academy of Sciences in 1779. Two years later Buffon named Lamarck correspondent of the Jardin du Roi, evidently to give Lamarck additional status while he escorted Buffons son on a scientific tour of Europe. This provided Lamarck with his first official connection, albeit an unsalaried one, with the Jardin du Roi. Shortly after Buffons death in 1788, his successor, Flahault de la Billarderie, created a salaried position for Lamarck with the title of botanist of the King and keeper of the Kings herbaria.

Between 1783 and 1792 Lamarck published three large botanical volumes for the Encyclopédie méthodique (Methodical Encyclopaedia) , a massive publishing enterprise begun by French publisher Charles-Joseph Panckoucke in the late 18th century. Lamarck also published botanical papers in the Mémoires of the Academy of Sciences. In 1792 he cofounded and coedited a short-lived journal of natural history, the Journal dhistoire naturelle.

Lamarcks career changed dramatically in 1793 when the former Jardin du Roi was transformed into the Muséum National dHistoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). In the changeover, all 12 of the scientists who had been officers of the previous establishment were named as professors and coadministrators of the new institution; however, only two professorships of botany were created. The botanists Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines held greater claims to these positions, and Lamarck, in a striking shift of responsibilities, was made professor of the insects, worms, and microscopic animals. Although this change of focus was remarkable, it was not wholly unjustified, as Lamarck was an ardent shell collector. Lamarck then set out to classify this large and poorly analyzed expanse of the animal kingdom. Later he would name this group animals without vertebrae and invent the term invertebrate. By 1802 Lamarck had also introduced the term biology.

This challenge would have been enough to occupy the energies of most naturalists; however, Lamarcks intellectual aspirations ran well beyond that of reforming invertebrate classification. In the 1790s he began promoting the broad theories of physics, chemistry, and meteorology that he had been nurturing for almost two decades. He also began thinking about Earths geologic history and developed notions that he would eventually publish under the title of Hydrogéologie (1802). In his physico-chemical writings, he advanced an old-fashioned, four-element theory that was self-consciously at odds with the revolutionary advances of the emerging pneumatic chemistry of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. His colleagues at the Institute of France (the successor to the Academy of Sciences) saw Lamarcks broad theorizing as unscientific system building. Lamarck in turn became increasingly scornful of scientists who preferred small facts to larger, more important ones. He began to characterize himself as a naturalist-philosopher, a person more concerned with the broader processes of nature than the details of the chemists laboratory or naturalists closet.

In 1800 Lamarck first set forth the revolutionary notion of species mutability during a lecture to students in his invertebrate zoology class at the National Museum of Natural History. By 1802 the general outlines of his broad theory of organic transformation had taken shape. He presented the theory successively in his Recherches sur lorganisation des corps vivans (1802; Research on the Organization of Living Bodies), his Philosophie zoologique (1809; Zoological Philosophy), and the introduction to his great multivolume work on invertebrate classification, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815–22; Natural History of Invertebrate Animals) . Lamarcks theory of organic development included the idea that the very simplest forms of plant and animal life were the result of spontaneous generation. Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first the power of life, or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex, whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment). He explained this in his Philosophie zoologique : The state in which we now see all the animals is on the one hand the product of the increasing composition of organization, which tends to form a regular gradation, and on the other hand that of the influences of a multitude of very different circumstances that continually tend to destroy the regularity in the gradation of the increasing composition of organization.

With this theory, Lamarck offered much more than an account of how species change. He also explained what he understood to be the shape of a truly natural system of classification of the animal kingdom. The primary feature of this system was a single scale of increasing complexity composed of all the different classes of animals, starting with the simplest microscopic organisms, or infusorians, and rising up to the mammals. The species, however, could not be arranged in a simple series. Lamarck described them as forming lateral ramifications with respect to the general masses of organization represented by the classes. Lateral ramifications in species resulted when they underwent transformations that reflected the diverse, particular environments to which they had been exposed.

By Lamarcks account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits. The basic idea of the inheritance of acquired characters had originated with Anaxagoras, Hippocrates, and others, but Lamarck was essentially the first naturalist to argue at length that the long-term operation of this process could result in species change.

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively Lamarckian view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited). The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarcks idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organisms lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.

Lamarck made his most important contributions to science as a botanical and zoological systematist, as a founder of invertebrate paleontology, and as an evolutionary theorist. In his own day, his theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Nonetheless, Lamarck stands out in the history of biology as the first writer to set forth—both systematically and in detail—a comprehensive theory of organic evolution that accounted for the successive production of all the different forms of life on Earth.

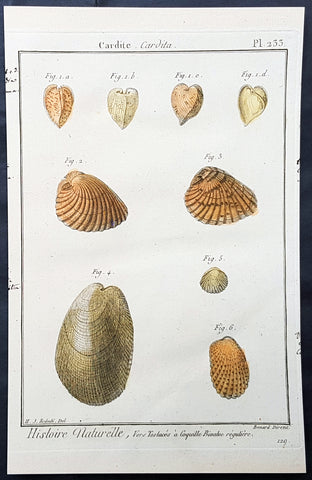

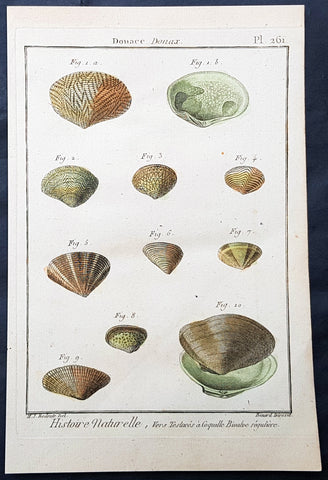

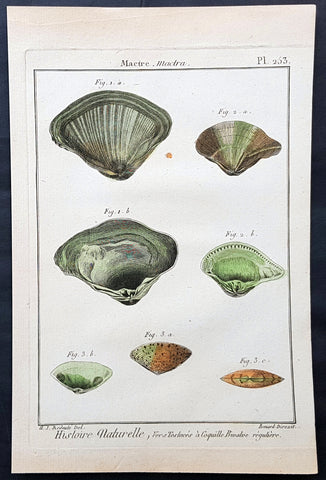

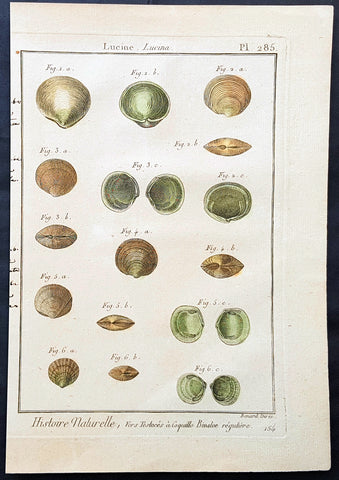

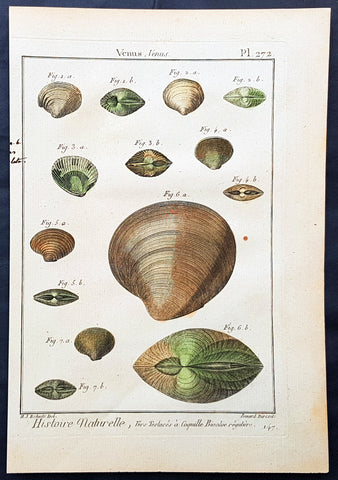

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Saltwater Clam Shells, Plate 233

- Title : Cardite, Cardita

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23864

Description:

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.

With Buffons support, Lamarck was elected to the Academy of Sciences in 1779. Two years later Buffon named Lamarck correspondent of the Jardin du Roi, evidently to give Lamarck additional status while he escorted Buffons son on a scientific tour of Europe. This provided Lamarck with his first official connection, albeit an unsalaried one, with the Jardin du Roi. Shortly after Buffons death in 1788, his successor, Flahault de la Billarderie, created a salaried position for Lamarck with the title of botanist of the King and keeper of the Kings herbaria.

Between 1783 and 1792 Lamarck published three large botanical volumes for the Encyclopédie méthodique (Methodical Encyclopaedia) , a massive publishing enterprise begun by French publisher Charles-Joseph Panckoucke in the late 18th century. Lamarck also published botanical papers in the Mémoires of the Academy of Sciences. In 1792 he cofounded and coedited a short-lived journal of natural history, the Journal dhistoire naturelle.

Lamarcks career changed dramatically in 1793 when the former Jardin du Roi was transformed into the Muséum National dHistoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). In the changeover, all 12 of the scientists who had been officers of the previous establishment were named as professors and coadministrators of the new institution; however, only two professorships of botany were created. The botanists Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines held greater claims to these positions, and Lamarck, in a striking shift of responsibilities, was made professor of the insects, worms, and microscopic animals. Although this change of focus was remarkable, it was not wholly unjustified, as Lamarck was an ardent shell collector. Lamarck then set out to classify this large and poorly analyzed expanse of the animal kingdom. Later he would name this group animals without vertebrae and invent the term invertebrate. By 1802 Lamarck had also introduced the term biology.

This challenge would have been enough to occupy the energies of most naturalists; however, Lamarcks intellectual aspirations ran well beyond that of reforming invertebrate classification. In the 1790s he began promoting the broad theories of physics, chemistry, and meteorology that he had been nurturing for almost two decades. He also began thinking about Earths geologic history and developed notions that he would eventually publish under the title of Hydrogéologie (1802). In his physico-chemical writings, he advanced an old-fashioned, four-element theory that was self-consciously at odds with the revolutionary advances of the emerging pneumatic chemistry of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. His colleagues at the Institute of France (the successor to the Academy of Sciences) saw Lamarcks broad theorizing as unscientific system building. Lamarck in turn became increasingly scornful of scientists who preferred small facts to larger, more important ones. He began to characterize himself as a naturalist-philosopher, a person more concerned with the broader processes of nature than the details of the chemists laboratory or naturalists closet.

In 1800 Lamarck first set forth the revolutionary notion of species mutability during a lecture to students in his invertebrate zoology class at the National Museum of Natural History. By 1802 the general outlines of his broad theory of organic transformation had taken shape. He presented the theory successively in his Recherches sur lorganisation des corps vivans (1802; Research on the Organization of Living Bodies), his Philosophie zoologique (1809; Zoological Philosophy), and the introduction to his great multivolume work on invertebrate classification, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815–22; Natural History of Invertebrate Animals) . Lamarcks theory of organic development included the idea that the very simplest forms of plant and animal life were the result of spontaneous generation. Life became successively diversified, he claimed, as the result of two very different sorts of causes. He called the first the power of life, or the cause that tends to make organization increasingly complex, whereas he classified the second as the modifying influence of particular circumstances (that is, the effects of the environment). He explained this in his Philosophie zoologique : The state in which we now see all the animals is on the one hand the product of the increasing composition of organization, which tends to form a regular gradation, and on the other hand that of the influences of a multitude of very different circumstances that continually tend to destroy the regularity in the gradation of the increasing composition of organization.

With this theory, Lamarck offered much more than an account of how species change. He also explained what he understood to be the shape of a truly natural system of classification of the animal kingdom. The primary feature of this system was a single scale of increasing complexity composed of all the different classes of animals, starting with the simplest microscopic organisms, or infusorians, and rising up to the mammals. The species, however, could not be arranged in a simple series. Lamarck described them as forming lateral ramifications with respect to the general masses of organization represented by the classes. Lateral ramifications in species resulted when they underwent transformations that reflected the diverse, particular environments to which they had been exposed.

By Lamarcks account, animals, in responding to different environments, adopted new habits. Their new habits caused them to use some organs more and some organs less, which resulted in the strengthening of the former and the weakening of the latter. New characters thus acquired by organisms over the course of their lives were passed on to the next generation (provided, in the case of sexual reproduction, that both of the parents of the offspring had undergone the same changes). Small changes that accumulated over great periods of time produced major differences. Lamarck thus explained how the shapes of giraffes, snakes, storks, swans, and numerous other creatures were a consequence of long-maintained habits. The basic idea of the inheritance of acquired characters had originated with Anaxagoras, Hippocrates, and others, but Lamarck was essentially the first naturalist to argue at length that the long-term operation of this process could result in species change.

Later in the century, after English naturalist Charles Darwin advanced his theory of evolution by natural selection, the idea of the inheritance of acquired characters came to be identified as a distinctively Lamarckian view of organic change (though Darwin himself also believed that acquired characters could be inherited). The idea was not seriously challenged in biology until the German biologist August Weismann did so in the 1880s. In the 20th century, since Lamarcks idea failed to be confirmed experimentally and the evidence commonly cited in its favour was given different interpretations, it became thoroughly discredited. Epigenetics, the study of the chemical modification of genes and gene-associated proteins, has since offered an explanation for how certain traits developed during an organisms lifetime can be passed along to its offspring.

Lamarck made his most important contributions to science as a botanical and zoological systematist, as a founder of invertebrate paleontology, and as an evolutionary theorist. In his own day, his theory of evolution was generally rejected as implausible, unsubstantiated, or heretical. Today he is primarily remembered for his notion of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Nonetheless, Lamarck stands out in the history of biology as the first writer to set forth—both systematically and in detail—a comprehensive theory of organic evolution that accounted for the successive production of all the different forms of life on Earth.

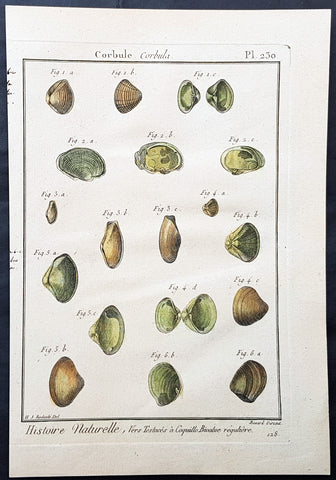

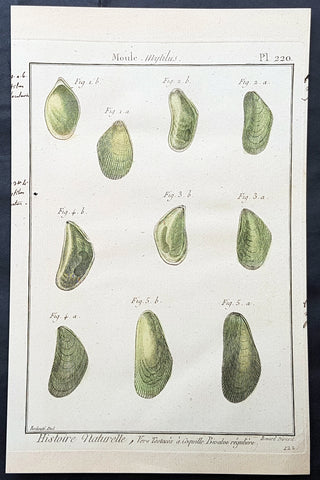

1789 Jean Baptiste Lamarck Antique Concology Print, Saltwater Clam Shells, Plate 230

- Title : Corbule, Corbula

- Size: 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Date : 1789

- Ref #: 23861

Description:

This fine original copper-plate engraved antique Conchology or Shell print by Jean Baptiste Lamarck was drawn by Henri Joseph Redoute (1766 - 1852) - younger brother of the famous illustrator P J Redoute - engraved by Robert Benard and published in the 1789 edition of Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature(1782-1832) by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - Off white

Age of map color: - Original

Colors used: - Yellow, Green, pink

General color appearance: - Authentic

Paper size: - 11in x 8in (280mm x 200mm)

Plate size: - 10in x 7in (255mm x 180mm)

Margins: - Min 1/2in (12mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois regnes de la nature was an illustrated encyclopedia of plants, animals and minerals, notable for including the first scientific descriptions of many species, and for its attractive engravings. It was published in Paris by Charles Joseph Panckoucke, from 1788 on. Although its several volumes can be considered a part of the greater Encyclopédie méthodique, they were titled and issued separately.

Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières (Methodical Encyclopedia by Order of Subject Matter) was published between 1782 and 1832 by the French publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke, his son-in-law Henri Agasse, and the latter´s wife, Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse. Arranged by disciplines, it was a revised and much expanded version, in roughly 210 to 216 volumes (different sets were bound differently), of the alphabetically arranged Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d Alembert.

Two sets of Diderots Encyclopédie and its supplements were cut up into articles. Each subject category was entrusted to a specialized editor, whose job was to collect all articles relating to his subject and exclude those belonging to others. Great care was to be taken of those articles that were of a doubtful nature, which were not to be omitted. For certain topics, such as air (which belonged equally to chemistry, physics and medicine), the methodical arrangement had the unexpected effect of breaking up a single article into several parts. Each volume was to have its own introduction, a table of contents, and a history of the Encyclopédie. The whole work was to be linked together by a Vocabulaire universel (Vol. 1 – 4), with references to all locations where each word appears.

The prospectus, issued early in 1782, proposed three editions, each with seven volumes of 250 to 300 plates:

84 volumes;

43 volumes, with 3 columns per page; and

53 volumes of about 100 sheets, with 2 columns per page.

The publication was continued by Henri Agasse, Panckouckes son-in-law, from 1794 to 1813, and then by the latters widow, Mme Agasse, until 1832, when it was completed in 102 livraisons or 337 parts, forming roughly 166½ volumes of text (depending on how the parts were bound) as well as 51 illustrated parts containing 6,439 plates. The number of pages totalled 124,210 pages, of which 5,458 pages were plates. To save money, the plates belonging to architecture were not published. Pharmacy (separated from chemistry), minerals, education, Ponts et chausses were not published as had been announced.

Many dictionaries have a classed index of articles. The one in Oeconomie politique is an excellent example, giving the contents of each article, so that any passage can be found easily.

When completed, the encyclopedia suffered at least one great weakness. As the Vocabulaire Universel, the key and index to the entire work, was not published, it was difficult to carry out any research or to find all the articles on any particular subject. The original parts had often been subdivided, and had been so added onto by other dictionaries, supplements, and appendices that an exact account could not be given of the work, which contained 88 alphabets, 83 indexes, 166 introductions, discourses, prefaces, etc. Overall, probably no more an unmanageable body of dictionaries has ever been published, except Jacques Paul Mignes Encyclopédie théologique, Paris, 1844–1875, with 168 volumes, 101 dictionaries, and 119,059 pages.

The Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières occupied a thousand workers in production, and 2,250 contributors.

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de1744 – 1829

Lamarck was a pioneer French biologist, who is best known for his idea that acquired characters are inheritable, an idea known as Lamarckism, which is controverted by modern evolutionary theorygenetics.

Lamarck was the youngest of 11 children in a family of the lesser nobility. His family intended him for the priesthood, but, after the death of his father and the expulsion of the Jesuits from France, Lamarck embarked on a military career in 1761. As a soldier garrisoned in the south of France, he became interested in collecting plants. An injury forced him to resign in 1768, but his fascination for botany endured, and it was as a botanist that he first built his scientific reputation.

Lamarck gained attention among the naturalists in Paris at the Jardin et Cabinet du Roi (the kings garden and natural history collection, known informally as the Jardin du Roi) by claiming he could create a system for identifying the plants of France that would be more efficient than any system currently in existence, including that of the great Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus. This project appealed to Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, who was the director of the Jardin du Roi and Linnaeuss greatest rival. Buffon arranged to have Lamarcks work published at government expense, and Lamarck received the proceeds from the sales. The work appeared in three volumes under the title Flore française (1778; French Flora). Lamarck designed the Flore française specifically for the task of plant identification and used dichotomous keys, which are classification tools that allow the user to choose between opposing pairs of morphological characters (see taxonomy: The objectives of biological classification) to achieve this end.