Exploration (3)

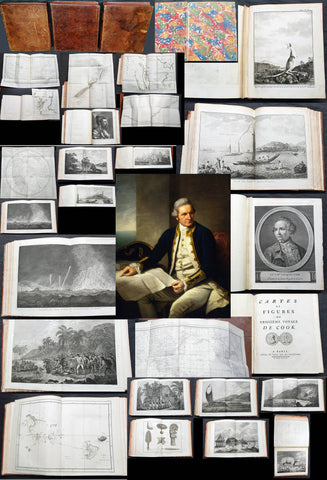

1774, 1777 & 1785 Capt James Cook 3 Atlas Volumes 1st Editions 204 Maps & Prints

- Title : 1. Figure du Banks 2. Premier Voyage De Cook 3. Troisieme Voyage De Cook

- Ref #: 93498, 93499, 93500

- Size: 4to (Quatro)

- Date : 1774; 1777; 1785

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

Description:

A unique and rare opportunity to acquire all three of Captain James Cooks 1st French edition Atlases (4to, Quatro), published to accompany the publication of his 3 voyages of discovery in 1774, 1777 & 1785. The atlases contain a total of 204 large folding, double page and single page maps and prints. It is very rare to find all three atlases complete and available together at the same time.

The contents of all three atlases are in fine condition, with a fresh, heavy impression and clean paper of all maps and prints.

As stated there are 204 maps and prints 51 in the 1st volume, 66 in the second volume and 87 in the second volume. Please view the images above, that include a few images of the 204 maps and prints as well as an itemized list of each volume.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - off white

Age of map color: -

Colors used: -

General color appearance: -

Paper size: - 4to (Quatro)

Plate size: - 4to (Quatro)

Margins: - 4to (Quatro)

Imperfections:

Margins: - Some scuffing and wear to boards & spines

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Timeline First Voyage 1768 - 1771:

In 1768 Cook was chosen to lead an expedition to the South Seas to observe the Transit of Venus and to secretly search for the unknown Great Southern Continent (terra australis incognita).

Cook and his crew of nearly 100 men left Plymouth (August 1768) in the Endeavour and travelled via Madeira (September), Rio de Janiero (November-December) and Tierra del Fuego (January 1769) to Tahiti.

At Tierra del Fuego (January 1769) Cooks men went ashore and met the local people whom Cook thought perhaps as miserable a set of People as are this day upon Earth. Joseph Bankss party collected botanical specimens but his two servants, Thomas Richmond and George Dorlton, died of exposure in the snow and cold. Leaving Tierra del Fuego Endeavour rounded Cape Horn and sailed into the Pacific Ocean.

Sir Joseph Banks wrote about the homes of the Fuegans

..…huts or wigwams of the most unartificial construction imaginable, indeed no thing bearing the name of a hut could possibly be built with less trouble. They consisted of a few poles set up and meeting together at the top in a conical figure, these were covered on the weather side with a few boughs and a little grass, on the lee side about one eighth part of the circle was left open and against this opening was a fire made.......(Banks, Journal I, 224, 20th January 1769)

Samuel Wallis on the ship Dolphin discovered Tahiti in 1767. He recommended the island for the Transit of Venus observations and Cook arrived here in April 1769. Cook, like Wallis two years before him, anchored his ship in the shelter of Matavai Bay on the western side of the island.

In Matavai Bay Cook established a fortified base, Fort Venus, from which he was to complete his first task – the observation of the Transit of Venus (3rd June 1769). The fort also served as protection for all the important scientific and other equipment which had to be taken ashore as:

.......great and small chiefs and common men are firmly of opinion that if they can once get possession of an thing it immediately becomes their own…the chiefs employd in stealing what they could in the cabbin while their dependents took every thing that was loose about the ship…...(Joseph Banks).

Theft by some native peoples plagued Cooks voyages.

Cook and his crew experienced good relations with the Tahitians and returned to the islands on many occasions, attracted by the friendly people of this earthly paradise. On arrival Cook had set out the rules, including:

.....To endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity....

Just as Cook was planning to leave Tahiti two members of Endeavours crew decided to desert, having strongly attached themselves to two girls, but Cook recovered them.

Cook sailed around the neighbouring Society Islands and took on board the Tahitian priest, Tupaia, and his servant, Taiata. Endeavour left the Society Island in August 1769.

Tupaia acted as interpreter when they came into contact with other Polynesian peoples and helped Cook to make a map of the Pacific islands. This showed Cook the location of islands arranged according to their distance from Tahiti and indicated Tupaias and Polynesian knowledge of navigation and their skill as great mariners.

Cook sailed in search of the Southern Continent (August-October 1769) before turning west to New Zealand. The first encounters with the native Maori of New Zealand in October were violent, their warriors performing fierce dances, or hakas, in attempts to threaten and challenge the ships crew. Some of their warriors were killed when Cooks men had to defend themselves. Eventually relations improved and Cook was able to trade with the Maori for fresh supplies.

Exploring different bays and rivers along the way Cook circumnavigated New Zealand and was the first to accurately chart the whole of the coastline. He discovered that New Zealand consisted of two main islands, north (Te Ika a Maui) and south (Te Wai Pounamu) islands (October 1769-March 1770).

The artist Sydney Parkinson described three Maori who visited the Endeavour on 12th October 1769:

......Most of them had their hair tied up on the crown of their heads in a knot…Their faces were tataowed, or marked either all over, or on one side, in a very curious manner, some of them in fine spiral directions…

This Maori wears an ornamental comb, feathers in a top-knot, long pendants from his ears and a heitiki, or good luck amulet, around his neck.

At the northern end of the south island Cook anchored the ship in Ship Cove, Queen Charlotte Sound, which became a favourite stopping place on the following voyages. Parkinson noted:

......The manner in which the natives of this bay (Queen Charlotte Sound) catch their fish is as follows: - They have a cylindrical net, extended by several hoops at the bottom, and contracted at the top; within the net they stick some pieces of fish, then let it down from the side of the canoe and the fish, going in to feed, are caught with great ease.....(Parkinson, Journal, 114)

In Queen Charlottes Sound Cook visited one of the many Maori hippah, or fortified towns.

........The town was situated on a small rock divided from the main by a breach in a rock so small that a man might almost Jump over it; the sides were every where so steep as to render fortifications iven in their way almost totally useless, according there was nothing but a slight Palisade…in one part we observed a kind of wooden cross ornamented with feathers made exactly in the form of a crucifix cross…we were told that it was a monument to a dead man.......

Endeavour left New Zealand and sailed along the east coast of New Holland, or Australia, heading north (April-August 1770). Cook started to chart the east coast and on 29th April landed for the first time in what Cook called Stingray, later, Botany Bay.

The ship struck the Great Barrier Reef and was badly damaged (10 June). Repairs had to be carried out in Endeavour River. (June-August 1770). The first kangaroo to be sighted was recorded and shot.

The inhabitants of New Holland were very different from the people Cook had come across in other Pacific lands. They were darker skinned than the Maori and painted their bodies:

......They were all of them clean limnd, active and nimble. Cloaths they had none, not the least rag, those parts which nature willingly conceals being exposed to view compleatly uncovered......(Joseph Banks)

Tupaia could not make himself understood and at first the aborigines were very wary of the visitors and not at all interested in trading.

Joseph Banks recorded the fishing party observed at Botany Bay on 26 April 1770. He wrote:

......Their canoes… a piece of Bark tied together in Pleats at the ends and kept extended in the middle by small bows of wood was the whole embarkation, which carried one or two…people…paddling with paddles about 18 inches long, one of which they held in either hand.....(Banks, Journal II, 134)

Endeavour left Australia and sailed via the Possession Isle and Endeavour Strait for repairs at Batavia, Java (October-December 1770). Although the crew had been quite healthy and almost free from scurvy, the scourge of sailors, many caught dysentery and typhoid and over thirty died at Batavia or on the return journey home via Cape Town, South Africa (March-April 1771). The ship arrived off Kent, England (July 1771).

The voyage successfully recorded the Transit of Venus and largely discredited the belief in a Southern Continent. Cook charted the islands of New Zealand and the east coast of Australia and the scientists and artists made unique records of the peoples, flora and fauna of the different lands visited.

Timeline - Second Voyage 1772 - 1775

In July 1772 Resolution, commanded by Captain Cook, and Discovery, commanded by Lieutenant Furneaux, set sail from Britain, via Madiera (Jul-Aug) and Cape Town, South Africa (Oct-Nov), towards the Antarctic in search of the Great Southern Continent.

During January 1773 the ships took on fresh water, charts of the voyage being marked with:

......Here we watered our Ship with Ice the 1st. Time 26S 44W and Here we compleated our Water/26S 20W but became separated in thick fog: Here we parted company…. and The Resolutions Track after we parted Company on the 8 of February 1773......

The ships became the first known to have crossed the Antarctic Circle (17 January 1773). On 9th January Cook wrote:

.......we hoisted out three Boats and took up as much as yielded about 15 Tons of Fresh Water, the Adventure at the same time got about 8 or 9 and all this was done in 5 or 6 hours time; the pieces we took up and which had broke from the Main Island, were very hard and solid, and some of them too large to be handled so that we were obliged to break them with our Ice Azes before they could be taken into the Boats...... Cook, Journals II, 74.)

The ships met again in New Zealand (February-May 1773) and set off to explore the central Pacific, calling at Tahiti (August), where, from the island of Raiatea, they took aboard Omai who returned with the Adventure to England (7 September).

After visiting Amsterdam and Middelburg, two islands that Cook called the Friendly Islands (Tongan group) (October) the ships became separated and never met again. Both ships returned separately to New Zealand. (November) A boats crew from the Adventure were killed by Maori (17 December) and the ship sailed for Britain, arriving July 1774.

Cook on Resolution attempted another search for the Great Southern Continent (November 1773), crossing the Antarctic Circle on 20th December 1773. However, the ice and cold soon forced him to turn north again and he made another search in the central Pacific for the Great Southern Continent. In January 1774 he turned south again, crossing the Antarctic Circle for the second time. Captain Cooks Journal, 2nd January 1774.

Cook sailed north, arriving at Easter Island in March 1774. Cook was too ill to go ashore but a small party explored the southern part of the island. The artist William Hodges painted a group of the large statues of heads (moia) for which the island has become famous.

Cook then sailed to the Marquesas (March); Tahiti (April) and Raiatea (June); past the Cook Islands and Niue, or Savage Islands as Cook called them; Tonga (June); Vatoa, the only Fijian Island visited by Cook (July); New Hebrides (July-August); New Caledonia (September) and Norfolk Island (October); before returning to New Zealand (October 1774).

Not all the peoples of the islands visited by Cook were friendly and when his ship approached Niue the local people would not let his crew ashore. Cook wrote:

.......The Conduct and aspect of these Islanders occasioned my giving it the Name of Savage Island, it lies in the Latitude of 19 degrees 1 Longitude 169 degrees 37 West, is about 11 Leagues in circuit, of a tolerable height and seemingly covered with wood amongst which were some Cocoa-nutt trees......(Cook, Journals II, 435, 22 June 1774.)

En route for New Zealand, Cook sailed west and explored the islands which he called the New Hebrides, now known as Vanuatu, arriving on 17 July 1774. The people were Melanesian, not Polynesian, and spoke different languages and had different customs. Cook recorded:

........The Men go naked, it can hardly be said they cover their Natural parts, the Testicles are quite exposed, but they wrap a piece of cloth or leafe round the yard (nautical slang for the penis) which they tye up to the belly to a cord or bandage which they wear round the waist just under the Short ribs and over the belly and so tight that it was a wonder to us how they could endure it.......(Cook, Journals II, 464, 23 July 1774)

Cook sailed past or visited nearly all the islands in the group, including landfalls at Malekula, Tanna and Erromango. He later moved on to New Caledonia.

Cooks reception by the New Hebrideans was generally hostile. At Erromango during the landing on 4th August 1774 the marines had to open fire when the natives tried to seize the boat and started to fire missiles. Cook wrote:

....…I was very loath to fire upon such a Multitude and resolved to make the chief a lone fall a Victim to his own treachery…happy for many of these poor people not half our Musquets would go of otherwise many more must have fallen.......(Cook, Journals II, 479, 4th August 1774)

Some of Cooks crew were slightly injured but several natives were wounded and their leader killed. Back on the ship Cook had a gun fired to frighten off the islanders and decided to depart.

Cook left New Zealand to return to Britain via the Southern Ocean in November 1774 and arrived in Tierra del Fuego, South America, in December. Cook took on stores and spent the holiday in what he called Christmas Sound. He described the area:......except those little tufts of shrubbery, the whole country was a barren Tack (or Rock) doomed by Nature to everlasting sterility......(Cook, Ms Journal PRO Adm 55/108)

Cook left South America in early January 1775 and set off across the southern Atlantic for Cape Town, South Africa. On the way he tried to confirm the location of a number of islands charted by Alexander Dalrymple on an earlier voyage. On 17 January 1775 Cook arrived at the cold, bleak, glaciated island he called South Georgia and spent 3 days charting it before sailing on.

Cook headed east and in late January came across the South Sandwich Islands that he again charted and then sailed on to Cape Town, arriving in late March 1775. He then headed across the Atlantic via St. Helena and Ascension Island (May), the Azores (July) and landed at Portsmouth on 30th July 1775.

On his return Cook became a national hero. He was presented to the King, made a member of the Royal Society and received its Copley Medal for achievement. Cook was promoted to post-captain of Greenwich Hospital and wrote up his account of the voyage. This did not mean retirement for Cook who went on his third and final voyage the following year.

The second voyage was one of the greatest journeys of all time. During the three years the ships crews had remained healthy and only four of the Resolutions crew had died. Cook disproved the idea of the Great Southern Continent; had become the first recorded explorer to cross the Antarctic Circle; and had charted many Pacific islands for the first time.

Timeline - Third Voyage 1776 - 1780

In 1776 Cook sailed in a repaired Resolution (July) to search for the North West Passage and to return Omai to his home on Huahine in the Society Islands.

He sailed via the Canary Islands and was joined at Cape Town, South Africa, by the Discovery, commanded by Charles Clerke.

The Discovery was the smallest of Cooks ships and was manned by a crew of sixty-nine. The two ships were repaired and restocked with a large number of livestock and set off together for New Zealand ( December).

Cook sailed across the South Indian Ocean and confirmed the location of Desolation Island, later known as Kerguelen Island. Cook wrote of Christmas Harbour where he first anchored on 25th December 1776:

........I found the shore in a manner covered with Penguins and other birds and Seals…so fearless that we killed as ma(n)y as we chose for the sake of their fat or blubber to make Oil for our lamps and other uses… Here I displayd the British flag and named the harbour Christmas harbour as we entered it on that Festival........(Cook, Journals III, i, 29-32)

Cook sailed east, arriving at Van Diemens Land/Tasmania (January 1777) and Queen Charlottes Sound, New Zealand (February). The Maori were wary at first, expecting Cook to take revenge for the killing of members of the Adventures crew in 1773, but instead Cook befriended the leader of the attack.

The ships stayed for nearly two weeks in New Zealand, restocking with wild celery and scurvy grass and trading with the local Maori who set up a small village in Ship Cove. Cook set off around the islands of the south Pacific (February), visiting the Cook Islands (April); Tongan Islands (July); and Tahiti (August-December 1777)

In 1778 Cook visited the Hawaiian islands, or Sandwich Islands as he named them, for the first time. Cook wrote:

........We no sooner landed, that a trade was set on foot for hogs and potatoes, which the people gave us in exchange for nails and pieces of iron formed into some thing like chisels….At sun set I brought every body on board, having got during the day Nine tons of water….about sixty or eighty Pigs, a few Fowls, a quantity of potatoes and a few plantains and Tara roots.......(Cook, Journals III, i. 269 & 272)

In February 1778 Cook sailed from the Hawaiian Islands across the north Pacific to the Oregan coast of North America. He travelled up the coast in bad weather until he found a safe harbour, Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island, Canada. There he refitted the ships, explored the area and developed relations with the local people.

Cook described a village there, probably Yoquot:

….their houses or dwellings are situated close to the shore…Some of these buildings are raised on the side of a bank, theses have a flooring consisting of logs supported by post fixed in the ground….before these houses they make a platform about four feet broad…..so allows of a passage along the front of the building: They assend to this passage (along the front of the building) by steps, not unlike some at our landing places in the River Thames........(Cook, Journals III, i, 306)

Cook left Nootka Sound in April 1778 and sailed north along the Alaskan coast looking for inlets that might lead to the Northwest passage but was then forced to turn south. By July he had rounded the Alaskan Peninsula and was able to sail north again, visiting the Chukotskiy Peninsula, Russia, before heading out into the Bering Sea.

Cook described the summer huts, or yarangas, of the Chukchi people as:

.........pretty large, and circular and brought to a point at the top; the framing was of slight poles and bone, covered with the skins of Sea animals…About the habitations were erected several stages ten or twelve feet high, such as we had observed on some part of the American coast, they were built wholly of bones and seemed to be intended to dry skins, fish &ca. upon, out of reach of their dogs........(Cook, Journals III, I, 413)

After entering the Bering Sea on 11th August 1778, Cook crossed the Arctic Circle and went as far north as latitude 70 degrees 41 North before being forced back by the pack ice off Icy Cape, Alaska. On the ice all around the ships were large numbers of walruses. About a dozen of these huge animals were killed to replenish the supplies of fresh meat and to provide oil for the lamps.

Cook had to turn west and worked his way down the Russian coast, eventually heading south and east into Norton Sound, Alaska, in September 1778. He wrote of their very brief encounter with the inhabitants of Norton Sound:

....…a family of the Natives came near to the place where we were taking off wood…I saw no more than a Man, his wife and child…...(Cook, Journals III, I, 438)

After a short period spent searching for the Northwest Passage Cook realised that it was too late in the year to make any progress and so sailed for warmer winter quarters in the Hawaiian Islands, arriving there in December 1778.

After circumnavigating the big island of Hawaii for over a month the ships finally anchored in Kealakekua Bay on 16th January 1779. The Hawaiians in over 1000 canoes came out to welcome them, the arrival of the ships coinciding with celebrations to mark the religious festival of Makahiki to the god Lono. The Hawaiians seem to have treated Cook as a personification of the god and at first relations were good on this second visit. However, relationships became strained and Cook left the island on 4th February 1779.

When Cook left Hawaii his ships ran into gales which broke a mast, forcing him to return to Kealakekua Bay for repairs on 11th February. This time the native people were less friendly and stole the cutter of the Discovery. The next day, the 14th February 1779, Cook went ashore to take the Hawaiian king into custody pending the return of the cutter but a fight developed and Cook, four of his marines and a number of natives were killed. Cooks remains were buried at sea in Kealakekua Bay.

Charles Clerke took over command of the stunned expedition and explored the other Hawaiian islands before sailing north to search for the North-West Passage. The ships called at Kamchatka, Russia, (April-June) where they were welcomed by the governor, Behm, at Bolsheretsk. Behm took news of the expedition and Cooks death overland to St. Petersburg from where it reached Europe and Britain.

Having made another voyage into the Arctic in search of the Northwest Passage (June-July) the ships returned to Kamchatka in August. In November they set off sailing south along the east coast of Japan, between Taiwan and the Phillipines and arrived at Macao, China, in December.

In January 1780 the expeditions left for home, crossing the Indian Ocean, calling at Cape Town (April-May) and arriving back in Stromness, Orkney, in August but not returning to London until October 1780.

News of Cooks death reached Britain in January 1780, ahead of the return of Resolution and Discovery in October 1780. The voyage was written up and published and Cooks life gradually commemorated in articles, books, medals and monuments.

The achievements of the voyage were overshadowed by the deaths of both Cook and his second-in-command, Clerke. The main purpose of the voyage, the discovery of the Northwest Passage, was not realised but large tracts of the Pacific and Arctic coasts of America and Russia were charted.

Early attempts to summarise the life of Cook appeared in the popular press soon after news of his death reached Britain. Articles in journals such as the Westminster Magazine, published in January 1780, included Biographical Anecdotes of Capt. Cook, charting his life from his birth in Marton, North Yorkshire. The first published biography of Cook, Life of Captain James Cook, by Andrew Kippis, appeared a few years later in 1788.

1669 Montanus Antique Print Sanjūsangen-dō 三十三間堂 Buddhist Temple Kyoto, Japan

- Title : Temple ou il y a 1000 Idoles: Temple met Duysend Beelden

- Date : 1669

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Ref # : 23413

- Size : 14 1/2in x 9in (360mm x 230mm)

Description:

This original copper-plate engraved antique print of Sanjūsangen-dō (三十三間堂) a Buddhist temple in Higashiyama District of Kyoto, Japan (with 1000 Kannon statues) during the Edo period, by Arnoldus Montanus was published in the 1669 edition of Gedenkwaerdige Gesantschappen der Oost-Indische Maetschappy int Vereenigde Nederland, aen de Kaisaren van Japan. Getrokken uit de Geschriften en Reiseaentekeninge der zelver Gesanten (Atlas Japannensis being remarkable addresses by way of Embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces, to the Emperor of Japan)

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - off white

Age of map color: -

Colors used: -

General color appearance: -

Paper size: - 15in x 12in (380mm x 305mm)

Plate size: - 13in x 10in (330mm x 255mm)

Margins: - Min 1in (20mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Sanjūsangen-dō (三十三間堂, lit. thirty-three ken (length) hall) is a Buddhist temple in Higashiyama District of Kyoto, Japan. Officially known as Rengeō-in (蓮華王院), or Hall of the Lotus King, Sanjūsangen-dō belongs to and is run by the Myōhō-in temple, a part of the Tendai school of Buddhism. The temple name literally means Hall with thirty three spaces between columns, describing the architecture of the long main hall of the temple.

Taira no Kiyomori completed the temple under order of Emperor Go-Shirakawa in 1164. The temple complex suffered a fire in 1249 and only the main hall was rebuilt in 1266. In January, the temple has an event known as the Rite of the Willow (柳枝のお加持), where worshippers are touched on the head with a sacred willow branch to cure and prevent headaches. A popular archery tournament known as the Tōshiya (通し矢) has also been held here, beside the West veranda, since the Edo period. The duel between the famous warrior Miyamoto Musashi and Yoshioka Denshichirō, leader of the Yoshioka-ryū, is popularly believed to have been fought just outside Sanjūsangen-dō in 1604.

The main deity of the temple is Sahasrabhuja-arya-avalokiteśvara or the Thousand Armed Kannon. The statue of the main deity was created by the Kamakura sculptor Tankei and is a National Treasure of Japan. The temple also contains one thousand life-size statues of the Thousand Armed Kannon which stand on both the right and left sides of the main statue in 10 rows and 50 columns. Of these, 124 statues are from the original temple, rescued from the fire of 1249, while the remaining 876 statues were constructed in the 13th century. The statues are made of Japanese cypress clad in gold leaf. The temple is 120 - meter long[1]. Around the 1000 Kannon statues stand 28 statues of guardian deities. There are also two famous statues of Fūjin and Raijin.

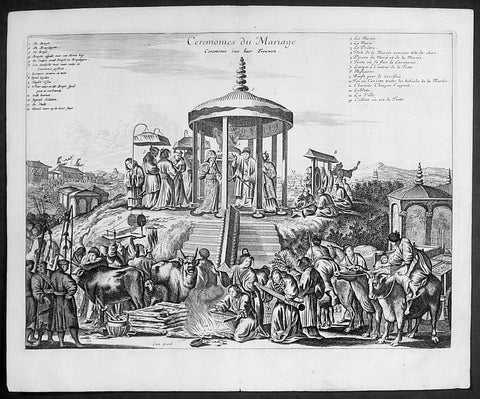

1669 Arnoldus Montanus Large Antique Print of a Japanese Marriage Ceremony 結婚式

- Title : Ceremonies du Mariage

- Date : 1669

- Condition: (A+) Fine Condition

- Ref # : 23411-1

- Size : 14 1/2in x 9in (360mm x 230mm)

Description:

This original copper-plate engraved antique print of a Japanese Marriage Ceremony during the early Edo period of Japanese history, by Arnoldus Montanus was published in the 1669 edition of Gedenkwaerdige Gesantschappen der Oost-Indische Maetschappy int Vereenigde Nederland, aen de Kaisaren van Japan. Getrokken uit de Geschriften en Reiseaentekeninge der zelver Gesanten (Atlas Japannensis being remarkable addresses by way of Embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces, to the Emperor of Japan)

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - off white

Age of map color: -

Colors used: -

General color appearance: -

Paper size: - 15in x 12in (380mm x 305mm)

Plate size: - 13in x 10in (330mm x 255mm)

Margins: - Min 1in (20mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

Marriage in the Edo period (1600–1868)

In pre-modern Japan, marriage was inextricable from the ie (家, family or household), the basic unit of society with a collective continuity independent of any individual life. Members of the household were expected to subordinate all their own interests to that of the ie, with respect for an ideal of filial piety and social hierarchy that borrowed much from Confucianism. The choice to remain single was the greatest crime a man could commit, according to Baron Hozumi.

Marriages were duly arranged by the head of the household, who represented it publicly and was legally responsible for its members, and any preference by either principal in a marital arrangement was considered improper. Property was regarded to belong to the ie rather than to individuals, and inheritance was strictly agnatic primogeniture. A woman (女) married the household (家) of her husband, hence the logograms for yome (嫁, wife) and yomeiri (嫁入り, marriage, lit. wife entering).

In the absence of sons, some households would adopt a male heir (養子, or yōshi) to maintain the dynasty, a practice which continues in corporate Japan. Nearly all adoptions are of adult men. Marriage was restricted to households of equal social standing (分限), which made selection a crucial, painstaking process. Although Confucian ethics encouraged people to marry outside their own group, limiting the search to a local community remained the easiest way to ensure an honorable match. Approximately one-in-five marriages in pre-modern Japan occurred between households that were already related.

Outcast communities such as the Burakumin could not marry outside of their caste, and marriage discrimination continued even after an 1871 edict abolished the caste system, well into the twentieth century. Marriage between a Japanese and non-Japanese person was not officially permitted until 14 March 1873, a date now commemorated as White Day. Marriage with a foreigner required the Japanese national to surrender his or her social standing.

The purposes of marriage in the medieval and Edo periods was to form alliances between families, to relieve the family of its female dependents, to perpetuate the family line, and, especially for the lower classes, to add new members to the family\'s workforce. The seventeenth-century treatise Onna Daigaku (Greater Learning for Women) instructed wives honor their parents-in-law before their own parents, and to be courteous, humble, and conciliatory towards their husbands.

Husbands were also encouraged to place the needs of their parents and children before those of their wives. One British observer remarked, If you love your wife you spoil your mother\'s servant. The tension between a housewife and her mother-in-law has been a keynote of Japanese drama ever since.

Romantic love (愛情, aijō) played little part in medieval marriages, as emotional attachment was considered inconsistent with filial piety. A proverb said, Those who come together in passion stay together in tears. For men, sexual gratification was seen as separate from conjugal relations with ones wife, where the purpose was procreation. The genre called Ukiyo-e (浮世絵, lit. floating world pictures) celebrated the luxury and hedonism of the era, typically with depictions of beautiful courtesans and geisha of the pleasure districts. Concubinage and prostitution were common, public, relatively respectable, until the social upheaval of the Meiji Restoration put an end to feudal society in Japan.